The Frankfurt school, part 2: Negative dialectics

Peter Thompson

프랑크푸르트 학파, 2부: 부정적 변증법

피터 톰슨

Unlike Hegel, Theodor Adorno rejected the idea the outcome of the dialectic will always be positive, and preordained

헤겔과 달리 테오도르 아도르노는 변증법의 결과가 항상 긍정적이며 미리 정해져 있다는 생각을 거부했다

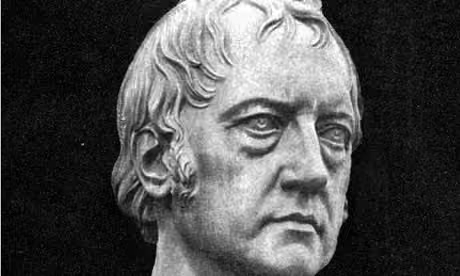

Adorno criticised Hegel, above, for presenting a positive and affirmative dialectic in which ‘everything that is real is rational’.”

아도르노는 위의 헤겔을 ‘현실적인 모든 것은 이성적이다’라는 긍정적이고 순응적인 변증법을 제시했다고 비판했다.

Already in the comments about the first instalment of this series, a problem of traditions has emerged. For a predominantly Anglo-Saxon audience, raised in the empirical and positivist tradition, understanding a group of thinkers schooled in speculative Hegelianism and Marxist dialectics is always going to require a leap of faith. This is also compounded by the fact that the largely monoglot Anglo-Saxon tradition has to work with translations of these thinkers, which are not always the best that can be achieved.

이 시리즈의 첫 번째 편에 대한 논평들에서 이미 전통의 문제가 대두되었다. 경험론적이고 실증주의적인 전통 속에서 자란 주로 앵글로색슨 독자들에게, 헤겔식 사변주의와 마르크스주의 변증법에 정통한 사상가 집단을 이해하는 것은 언제나 믿음의 도약을 요구한다. 이것은 또한 주로 단일 언어권인 앵글로색슨 전통이 이들 사상가들의 번역본들에 의존해야 한다는 사실로 인해 더욱 복잡해지는데, 이것들이 항상 성취될 수 있는 최상은 아니기 때문이다.

For example, terms such as Wissenschaft and Geist traditionally get translated into “science” and “spirit”, apparently irreconcilable opposites, whereas in philosophical terms the difference between the two is much less marked. In fact, you might argue that in the original German they could both be translated as “knowledge”, albeit different types of knowledge bounded by speculation. When it comes to the Frankfurt school, the Anglo-Saxon tradition is confronted with all of its worst nightmares in one torrid night of speculative muscle flexing.

예를 들어, Wissenschaft와 Geist 같은 용어들은 전통적으로 “과학”과 “정신”으로 번역되어 표면상 화해할 수 없는 대립항들로 여겨지지만, 철학적 용어들에서 이 둘의 차이는 훨씬 덜 뚜렷하다. 사실 원어인 독일어에서는 둘 다 “지식”으로 번역될 수 있다고 주장할 수도 있다. 비록 사변에 의해 제한된 서로 다른 유형의 지식이지만 말이다. 프랑크푸르트 학파에 이르러서는, 앵글로색슨 전통은 사변적 근육 과시의 무더운 한밤중에 그 최악의 악몽들을 모두 마주하게 된다.

Theodor Adorno opens his treatise on negative dialectics with the statement that “[it] is a phrase that flouts tradition. As early as Plato, dialectics meant to achieve something positive by means of negation; the thought figure of the ‘negation of the negation’ later became the succinct term. This book seeks to free dialectics from such affirmative traits without reducing its determinacy.” In other words, he asks us to reject the idea that the outcome of the dialectic will always be positive but that we do so without leaving the dialectic behind as an explanatory model. We simply have to make it an open rather than a closed process.

테오도르 아도르노는 부정적 변증법에 관한 자신의 논고를 “[이 용어는] 전통을 무시하는 표현이다. 플라톤 시대부터 변증법은 부정을 통해 긍정적 결과를 달성하려는 것이었으며, ‘부정의 부정’이라는 사고 형상이 후에 간결한 용어로 자리 잡았다. 이 책은 변증법의 결정성을 훼손하지 않으면서도 그러한 긍정적 특성으로부터 변증법을 해방시키려 한다”는 진술로 연다. 달리 말해, 그는 변증법의 결과가 항상 긍정적일 것이라는 생각을 거부하되, 설명 모델로서의 변증법을 버리지 말 것을 요구한다. 우리는 단순히 그것을 닫힌 과정이 아닌 열린 과정으로 만들어야 한다.

――

아도르노는 […] 연다

――

In Hegel the dialectic is widely seen as the means by which, through contradiction and tension, human history represents the unfolding of human freedom as the expression of the Weltgeist, or world spirit. Each age has its own zeitgeist (a sort of temporal appearance on Earth as the expression of the absolute – Christ as God come to Earth, if you like) but each of those ages is linked and taken up into (aufgehoben) the next succeeding one. Thus history is not just “one fucking thing after another”, as Alan Bennett has it, but a gradual accretion through contradiction of the necessary stages for the fulfilment of the absolute. As Ernst Bloch pointed out, werden, or “becoming”, was Hegel’s password and history was simply the process of becoming. The dialectic was thus the way to understand an old idea first put forward by Heraclitus that everything is constantly in flux, or panta rhei, that the basic condition of the world is change and not stability. But change towards what?

헤겔에게서 변증법은 모순과 긴장을 통해 인류 역사가 인간 자유의 전개를 Weltgeist, 또는 세계정신의 표현으로서 나타내는 수단으로 널리 인식된다. 각 시대는 그 자신의 Zeitgeist (절대자의 표현으로서의 일종의 일시적인 지상적 현현—예를 들어 지상에 내려온 신으로서의 그리스도)를 지니지만, 각 시대는 서로 연결되어 다음 시대로 포섭(aufgehoben, 지양)된다. 따라서 역사는, 앨런 베넷이 말한 것처럼, “그저 엿같은 일들이 연이어 일어나는 것”이 아니라, 모순을 통해 절대자의 완성을 위한 필수 단계들이 점진적으로 축적되는 것이다. 에른스트 블로흐가 지적했듯, werden, 또는 “생성”은 헤겔의 암호였고 역사는 단순히 생성의 과정이었다. 변증법은 헤라클레이토스가 처음 제시한 모든 것은 끊임없이 유동한다, 또는 panta rhei라는 오래된 사상을 이해하는 방식이었다. 즉 세상의 기본 조건은 안정성이 아니라 변화라는 것이다. 그러나 무엇으로의 변화인가?

――

그저 엿같은 일들이 연이어 일어나는 것

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2006/oct/17/theatre.schools

――

In Hegel it is the absolute and in Hegel’s most famous follower, Marx, it becomes the liberation of humanity in some form of communist society achieved by the conscious action of the proletariat in overcoming the final dialectical hurdle by abolishing the ruling class and thereby, logically, itself. The Marxist dialectic replaces the idealist Geist of a period working in mysterious ways with the concrete materialist class struggle as the engine of history, constantly present and constituting history as such.

헤겔에게 그것은 절대자이며, 헤겔의 가장 유명한 추종자 마르크스에게 그것은 지배 계급을 폐지하고 그럼으로써 논리적으로 그 자신도 폐지함으로써 최종 변증법적 장애물을 극복하는 프롤레타리아트의 의식적 행동에 의해 성취되는 어떤 형태의 공산주의 사회 속 인류의 해방이 된다. 마르크스주의 변증법은 신비로운 방식으로 작용하는 시대의 관념론적 Geist를, 끊임없이 현재하면서 역사 자체를 구성하는, 역사의 엔진으로서의구체적인 유물론적 계급 투쟁으로 대체한다.

As early as the end of the 19th century, this Marxist analysis had become “Hegelianised” in the sense that it was increasingly presented as an automatic and inevitable fulfilment of a preordained path. Adorno criticised Hegel for giving rise to this by presenting a positive and affirmative dialectic in which “everything that is real is rational”, in that everything that comes about must contribute in some way to the workings of the absolute. To use a technical term, this means that in Hegel there is an “identity of identity and non-identity”. In more ordinary language, Hegel is arguing that existence as a whole constitutes a unity of all opposites, in which everything has its place and that the tension between these opposites gradually resolves itself into pre-existing whole.

19세기 말에 이르러 이 마르크스주의적 분석은 점차 예정된 경로의 자동적이고 필연적인 성취로 제시되면서 “헤겔화”되었다. 아도르노는 헤겔이 발생하는 모든 것이 어떤 식으로든 절대자의 작용에 기여해야 한다는 점에서 “현실적인 모든 것은 이성적이다”라는 긍정적이고 순응적인 변증법을 제시함으로써 이것을 초래했다고 비판했다. 전문 용어로 말하자면, 이것은 헤겔에게는 “동일성과 비동일성의 동일성”이 있음을 의미한다. 좀 더 평이한 표현으로는, 헤겔은 존재 전체가 모든 대립항들의 통일체를 구성하며, 그 안에서 모든 것이 제자리를 차지하고, 이 대립항들 사이의 긴장이 점차 선재하는 전체로 해소된다고 주장한다.

Negative dialectics turns this on its head and says that there is a “non-identity of identity and non-identity” or that existence is incomplete, that it has a hole in it where the whole should be, that history is not the simple unfolding of some preordained noumenal realm and that existence is therefore “ontologically incomplete”. It is here that we find the link between Marx and Freud because, where Marx talks about the objective material factors at work in history that condition our consciousness (being determines consciousness) even though we are not necessarily conscious of them, Freud argues that it is our objective unconscious being, of which we are equally unaware, that determines our conscious thoughts. The latent content of our dreams is therefore equated with the latent but as yet unrealised possibilities in human history (see Marx’s letter to Ruge in my previous column).

부정적 변증법은 이것을 뒤집어 “동일성과 비동일성의 비동일성”이 있다고 말한다. 즉 존재는 불완전하며, 존재는 전체가 있어야 할 곳에 구멍이 있고, 역사는 미리 정해진 초월적 영역의 단순한 전개가 아니며, 따라서 존재는 “존재론적으로 불완전하다”는 것이다. 여기서 우리는 마르크스와 프로이트의 연결점을 발견한다. 마르크스가 우리의 의식을 조건 짓는, 역사 속에서 작동하는 객관적 물질적 요인들(존재가 의식을 규정한다)에 대해 얘기한다면, 프로이트는 우리의 의식적 사고를 규정하는 것은 우리가 마찬가지로 인식하지 못하는, 우리의 객관적 무의식적 존재라고 주장하기 때문이다. 따라서 우리 꿈의 잠재적 내용은 인간 역사 속 잠재적이지만 아직 실현되지 않은 가능성과 동일시된다(지난 칼럼에서 언급한 마르크스의 루게에게 보낸 편지 참조).

――

지난 칼럼

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/mar/25/anders-breivik-frankfurt-school

――

Adorno’s negative dialectics are designed to open up these as yet unrealised possibilities at both the micro and the macro level, at the level of individual as well as collective psychology in order to overcome both individual and social suffering. It is the very contradiction between what is and what might be that allows us to overstep the boundaries with which we are constantly presented in order to create our endpoint, rather than simply sleepwalk towards it. This means that we move from necessity to contingency. In negative dialectics there is no necessity for things to turn out in a certain way, and the future-orientated teleology that Adorno claimed Hegel followed is replaced with retrospective teleology in which we can only see that what has happened to get us to where we are had to happen to get us there, but that there was no necessity for it happen in that way. Human beings are a product of evolution but evolution is not there to create human beings. Walter Benjamin famously expressed this as the angel of history moving backwards into the future with the debris of history piling up around his feet. Negative dialectics are, in the end then, open dialectics conditioned by contingent events and not by a pre-given endpoint.

아도르노의 부정적 변증법은 개인적 고통과 사회적 고통 둘 다 극복하기 위해 개인 심리 수준과 집단 심리 수준에서, 즉 미시적 수준과 거시적 수준 둘 다에서 이 아직 실현되지 않은 가능성들을 열어놓고자 고안되었다. 존재하는 것과 존재할 수 있는 것 사이의 모순이야말로 우리의 종착점을 창조하기 위해 우리가 끊임없이 마주하는 경계를 넘을 수 있게 한다. 그것을 향해서 단순히 몽유병 환자처럼 걸어가기보다는 말이다. 이것은 우리가 필연성에서 우발성으로 이동함을 의미한다. 부정적 변증법에서는 사물이 특정 방식으로 전개될 필연성이 없으며, 아도르노가 헤겔이 따랐다고 주장한 미래 지향적 목적론은 회고적 목적론으로 대체된다. 회고적 목적론에서는 우리가 현재 위치에 도달하기까지 일어난 일들이 그곳에 도달하려면 일어나야만 했지만, 그것이 그런 방식으로 일어날 필연성은 없었다는 것만을 볼 수 있다. 인간은 진화의 산물이지만, 진화는 인간을 창조하기 위해 있지 않다. 발터 벤야민은 이것을 역사의 천사가 역사의 파편들이 발밑에 쌓여가는 가운데 미래로 거꾸로 걸어가는 모습으로 유명하게 표현했다. 결국 부정적 변증법은 미리 주어진 종착점이 아닌 우발적 사건들에 의해 조건지어진 열린 변증법이다.

――

발터 벤야민은 […] 표현했다

http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm

――

Next week I will look at how this works out in terms of an attempt to break out of the snow globe of western consumer capitalism. If you want to do some reading in preparation I would suggest the Dialectic of Enlightenment.

다음 주에는 서구 소비 자본주의의 눈송이 유리구슬에서 벗어나려는 시도가 어떻게 전개되는지 살펴보겠다. 미리 읽을 자료를 원하신다면 <계몽의 변증법>을 추천한다.